Nathan Ford

Born in London, 1976, Nathan Ford lives and works in Wales

Ford graduated from The Byam Shaw School of Art in 2000 and has since been shown in numerous solo and group exhibitions in Bath, London, and internationally. His work has been included in the BP Portrait Awards, winning the Visitors Choice Prize in 2011.

Ford grew up in London, and references to London’s landscape and architecture can be seen in his paintings, especially references to Norwood and Crystal Palace where he spent his childhood. Ford moved to a village in rural Wales in 2002. His family, especially his children Joachim and Reuben, feature heavily in his work, whether in the form of atmospheric, detailed portraits within sparse backgrounds, or within cityscapes. Ford’s work is a practice of sensitively considering and economising line, each brush stroke or pencil mark charged with meaning, memory, feeling.

To read the 2023 catalogue essay on Nathan’s work, please see the ‘writing’ tab at the top of this page.

You will also find a 12 minute film by Emmy Award-winning cameraman Michael Pitts via the ‘Film’ tab. A catalogue is available to purchase from the gallery.

Catalogue Essay 2023

At night you trap stars, and the moon

fills you with distances.

I arrange myself to put

one rose in the belt of Orion.

When the salt gales drag through you

you whip them with flowers

and I think –

Exclamations for you, little rose bush,

and a couple of fanfares.

From Praise of a Thorn Bush, Norman MacCaig

A Radio 4 discussion programme with Margaret Atwood stays with me. The oft-interviewed author is asked how she coped with the tumult of world events. She laconically responds that it was necessary to imagine the day’s challenges as a garden where one fenced off a manageable area, and then after a pause – that sometimes a morning coffee was as far as her own borders could encompass. This metaphor for dealing with life’s daily demands came to me again recently as Nathan and I talked in his studio, surrounded by a neat stack of his latest work.

Nathan is by nature a well-adjusted person. The tumultuous world is kept at arms length, and like any good artist, he chooses what moves him and seeks to impose form on it. The latest work can be broadly split into three categories – small spare still lifes; portraits, in this instance of family members only. Then there are larger format landscapes which incorporate aspects of the smaller work, and include frames painted well inside the edges, creating a story-within-a-story effect.

Nathan’s natural sense of order allows him space to conduct what he refers to as personal investigations, an obsessional mix of observational minutiae, quotidian practice, and the use of subject matter within his own temporal and physical environs. What has sufficient significance to draw and paint may to most of us seem non-descript. The smaller of the still life series are a continuation of an idea begun during lockdown; weeds and flowers gathered during the one daily permissible walk that the family took together. The subjects, including the artist himself, share something of the very nature of these flowers that blossom in such unlikely environments, plucked as they are off a stony Welsh hillside.

He sees the little still lifes as a celebration of the natural world. To someone born and raised in South London, you take nature how and where you find it – so a long panoramic painting showing a child striding past an outlined backdrop of tower-blocks, with accompanying fantastical stick-figure bees, stencilled pink aliens and empty bottles, is entitled Walled Garden. He would, he remembers, marvel at seed pods that would germinate in the oily pools of his Dad Stan’s garage, situated in East Place, another large canvas where the scrawny weeds are illuminated, echoing the style of the still lifes (see Winter 22 for example).

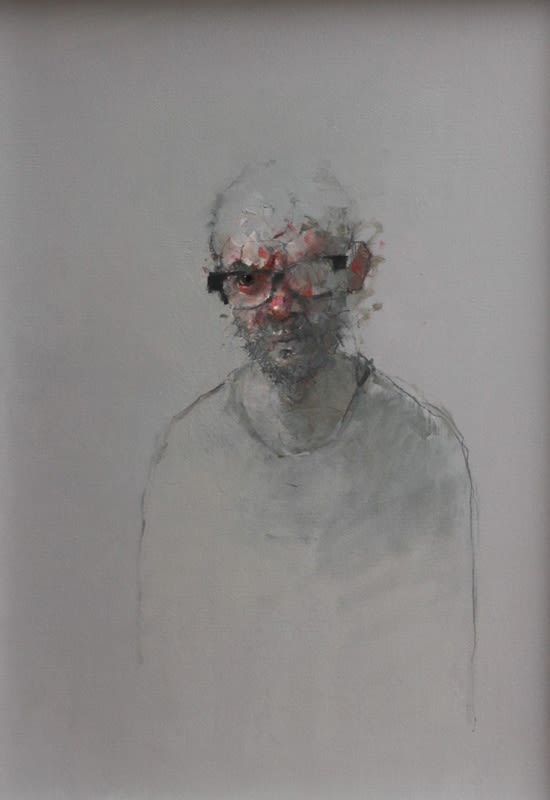

Sitting for Nathan is unnerving, as his long-suffering spouse and sons will corroborate. He is looking to strip away the game face. ‘I want to find the thing that scares me’, he puts it. Dyslexic as a young man, he is the kind of person who will work things out independently, from first principles. The ability to look for quiddity, to decode visual signals, is his singular talent, and so the hope is that these archetypes, wrought from a flaccid bunch of weeds well past their best, or in the face of a person whose character he has an intimate knowledge of, may draw in and be recognised in turn by a curious audience.

Shutting the world off is necessary for patient observation. It helps, he posits, to ’take myself out of the equation as much as possible, so I can see to paint.’ He also talks about the periphery of the work, or rather, seeing the work in peripheral vision. ‘What you see when you look past the painting, or seeing it in reflection, will help build an impression.’ The question of what one is actually seeing has long fascinated him. He regularly encounters a flock of sheep on an Iron Age hillfort outside Cardiff, and with weather, and crepuscular muddy light, ‘My brain completes the picture with background information, but what is it am I actually looking at?’ Without architectural detail to steady them, the sheep float in the murk. Nathan’s quiet greyish palette is ideal for the job at hand, lending depth and subtle colour to the inky gloaming. ‘I want the work to hum in the dark and pop in the light’, he explains.

So all the research, study, investigation, the muscle memory in his elegant painter’s hands, is an attempt to find and evoke essence, something done patiently over time. This may mean it is at first not clear where the painting finishes. He describes dialogue with the work, ‘The paintings talk to me, and sometimes (he says gesturing towards the window) they insist that I go out on to the hills again.’ Screen representations too can be distracting. ‘Seeing images of work, I have sometimes thought I got it wrong – then I go back to the work itself and realise, actually no – that was an honest and accurate evocation of that moment in time.’

The still lifes and portraits nourish the larger paintings. Sagging plants and flowers, sitters, are all familiar and endemic. There is no exoticism, flash or noise, beyond the obsession to create, to jettison superfluous detail, and quietly, as he puts it ‘crystallise things, bring things to a point’. He continues, ‘Sometimes you can recognise in a moment what it is to be, to live, and you can’t get air into your lungs quick enough.’ And a moment later, ‘Consciousness is the one thing we share and we haven’t got a clue how to talk about it.’

It is not only subject matter, or style, or talent, or the intolerance of superfluous detail that has allowed Nathan to make his work as distinctive as it is. It is not even the sheer bloody-minded honesty of it, or his ability to create works of quiet mystery out of things easily discarded. It is of course all these things, that spring from his life as a father and an artist. The little flowers clinging to life, the diminutive children, the hulking lorries, inner city walls with their cartoon insects and monsters – this inspired collection of work, it is obvious to me, is all of a piece. He is (to paraphrase the poet) – in the paintings, and the paintings in him. ‘The things I produce are not life, but they are symbols and marks which describe my interactions with life’.

As Yusef Komunyakaa says of his hero in Ode to the Maggot:

No decree or creed can outlaw you

As you take every living thing apart. Little

Master of earth, no one gets to heaven

Without going through you first.

Aidan Quinn

January 2023

Catalogue Essay 2021

Keep me away from the wisdom which does not cry, the philosophy which does not laugh and the greatness which does not bow before children. –Kahlil Gibran

Over two decades ago Nathan Ford first walked through the doors of the gallery, a shy but determined raw young artist. This exhibition marks his tenth solo show. To accompany this auspicious exhibition we have, with the help of renowned cameraman Michael Pitts, made a twelve minute film, Nathan Ford, Painter. Please see the tabs at the top of the page page for details.

With Nathan, the discomfiture to him of sitting in front of a camera and being interviewed was, I surmised, in direct proportion to the benefit of doing so. It was not quite a Groucho Marx-type paradox (where anyone who wants to be interviewed would not make a worthwhile interviewee). Some people, some artists, cope well with the required concision. Nathan would much prefer to show rather than tell, though I knew there was a good story to be wrought from his recalcitrance.

But where to start, and how to draw it out of a man unwilling to be caught in the cross-hairs of art-waffle for a nanosecond. I was aware that attempting to portray him expounding on the deeper hankerings of his oeuvre would be met with derision. There were consistent warnings, as stern as any of his portraiture eviscerations, that any artistic streams of consciousness were akin to him being unable to face his wife and children again. He arrived at the gallery under the false pretence that most of the day would be spent taking footage of him painting a portrait. A necessary inducement, as I was aware that drawing out a narrative would necessitate interview material, and that the edited result wouldn’t be what he feared. He is much too warm and personable a human being.

Nathan’s sons are 14 and 12 respectively and are heavily invested in Nathan’s work, as arbiters of good taste as much as makers of stencils, drafters of amorphous cartoon monsters, graffiti-scrawlers on cityscape walls. ‘They’ve got it’ he exclaims at one point, ‘Of course they’ve got it, they’re kids!’ And so Nathan is sceptical about art school, training, validation, and artists ‘fluffing around trying to make work that’s real.’ If nothing else his two boys have been stalwart markers of time throughout his career, his portraits charting their growth, their vulnerability still staring out at us a decade after he first allowed himself to paint them and to allow the public to see the results.

A body of work by Nathan is always recording the passage of time, whether portraits or the dusky European cityscapes of family vacations. Years back it was a tender depiction of Reuben’s ear as a child. In the BP prize exhibition of 2018, ‘Dad’s Last Day’ is a painting (in the moment) of exactly that. There is no equivocation here, no rosy nostalgic hue. His work comes hard and fast. East Place is the location of his dad Stan’s garage in South East London that he grew up in and around as a teenager; Sunny Inside is a another street scene in the West Norwood of his childhood. They have a fin de siècle feeling in them. That is what they are.

So his family are not only subjects in his portraits. Both sons do extensive work on the larger paintings themselves. He waxes lyrical about his children and is unabashedly proud of their achievements and projects, among them Joachim’s inspired and idiosyncratic music (used in the film), and Reuben’s coding (which helps run his website). However, it is evident that as choreographer and chief conductor Nathan is not stinting on the hard yards of work. There is the sheer practical reality that every pane of non-reflective glass, every mitre-joint of every tulip-wood frame is hand-cut, painted and sanded by Nathan himself. When it comes to his work and the presentation of it he is the definition of punctiliousness.

The larger paintings are painted on to birch panels, most of them in 122 x 170 cm. landscape format. Having previously painted on to canvas and linen, the use of birch is the result of extensive research, a gradual honing down of possibilities to find a surface with the ideal tooth to paint comfortably on, and to absorb the layers of primer, washes and oil paint in such a way as to preserve the delicate balance of Nathan’s ‘variations in the key of grey’ palette. ‘I fight the grey’ Nathan opines, ‘I try lots of different things and when I think I have fixed the painting I step back….and it’s grey again.’

The actual physical flatness of the surface, which will have been sanded back repeatedly between primer and base layers, is a contrast to the depth of the vistas within, which often incorporate streetscapes inclining or receding into the hum of evening light, on a Welsh hillside (Flock V) , or in a Sicilian town (La Scena). There is no impasto, no flash, no shiny, luscious oily dollops of paint. With detailed skeletal drawings underpinning the blocked-in matte colour of the overhanging buildings, you can smell south London in the brickwork, the pavements and scaffolding.

The 90 days of lockdown series of paintings more literally chronicle the passage of days, beginning on March 24th 2020 and carrying on for three months, one painting per day. The bunches of weeds; buttercup, clover, cow parsley, daisy, dandelion, wild sweet pea, wild strawberry, are a daily meditation on ‘looking’, their little bursts of colour and form imbued with the noise of quotidian news and events- new restrictions reported, casualty figures updated, events cancelled, protests in the U.S.

These little plants are Leonard Cohen’s heroes in the seaweed from Suzanne,

And the sun pours down like honey

On our lady of the harbour

And she shows you where to look

Among the garbage and the flowers

There are heroes in the seaweed

There are children in the morning

They are leaning out for love

And they will lean that way forever

While Suzanne holds the mirror

Nathan would take his place each day, his chair in its ordained position, the tilted canvas backdrop -allowing for the angle of eyes to subject- framing his votive cup of weeds, revivified by water or dead and almost completely dried out. From his station he would draw, drawing out of himself the process of daily observance, extracting the story of lockdown, living lockdown from an artistic and personal solitude, looking at bunches of offerings gathered at random on the one permitted family walk du jour.

These small lockdown paintings are a typical Fordian enterprise. His marking of time, family life woven into the works; the channelling of events and emotions from worlds within and without, show characteristic resolve. Their essence is narrow, in each touchingly precious little piece, and then broad in that they form one larger piece of work encapsulating three months of dedicated intensity. The cup is a canvas within a canvas, now here, now evanescing to make way for a barely visible saw-tooted leaf or dried-out weed stem.

Nathan’s 20 years of exhibitions have all been coming to this. His sharpened skills have turned lockdown into opportunity. ‘It’s an interesting chapter’ he intones gently, ‘but what can I do… but make a painting’. And with a shrug of his shoulders, I knew he was bringing the film to a close.

Aidan Quinn

February 2021

Catalogue Essay 2019

Anybody who preserves the ability to recognise beauty will never get old.

-Franz Kafka

Nathan Ford’s paintings are an essential part of his communication with the outside world. He marks the passing of time with portraits of his children, family and friends, all faces he knows beyond mere flesh. His larger works, mainly urban landscapes, are an exploration of fleeting sensations of light, form and colour. Still-lifes, with flowers on the point of dying, are in one sense momento mori, though Nathan bridles at such a direct allusion. ‘They are about remembering and forgetting. Even the process of painting them is helpful, despite the emotion being raw. But I wonder if I am telling myself stories. How can I know the truth of why exactly I am doing these paintings?’

This musing is appropriately Kafkaesque. He points to the initial inspiration for the figure in Platform as the main character in The Trial. We find our Jozef K looking suitably forlorn, legs splayed redundantly as he waits on a bench at Baker Street, dwarfed by the long cascading emptiness of the underground station.

Playfulness too is a vital feature in Nathan’s work, and the artist enthuses about the influence of his sons Reuben (12) and Joachim (10). Their drawings are prominent in Vicenza (cover image), among other works, and there is an unbridled inventiveness and joy in their own GreyHope paintings. A shared sense of humour and experience (see Smoking Fags at the Exit) are products of a strong family bond and a high mutual regard for creative endeavour and self-reliance. Indeed over the two decades I have known Nathan I have appreciated his quiet, determined single-mindedness. From choosing, cutting and finishing the wood for his frames, to the merest mark-making on the largest painting, Nathan approaches all aspects of his work, practical and artistic, with careful deliberation and focus. He has also found a rhythm in the sequence of processes involved in preparing for a biennial exhibition.

The appearance of his late father Stan highlights the emotional import of the larger works, something that may be more obvious in the portraits, where the concentration on the subjects’ eyes intensifies the ‘eye-contact’, or in the preoccupation with mortality in the still-lifes. Once attracted to look at his urban works one discovers that they have a compelling depth, due in no small part to the detailed architecture, carefully rendered though scarcely noticeable at first.

When describing why one of the larger landscapes grates, Nathan repeatedly remarks ‘It doesn’t work, I can’t inhabit it’. I imagine the artist standing before one of these paintings, the work sloping down in a curve towards his feet in the manner of a skateboard ramp, enlivening the sensation of stepping into the scene. Only within a solid and subtle composition is he unconfined and free to take us on a visual adventure, to enjoy the highlighted areas of emphasis, or to follow a light trail into darker recesses, and the smells and fluid buzz of a city thoroughfare.

Though family is a thread woven deep into the work, the paintings are not historical or sentimental. There are streets we may feel we recognise, and actual locations in south-east London, some of them framed within painted black lines which give them the feel of looking at old negatives. We see Crystal Palace and Herne Hill, or the Brighton sea-front. Ford attests however that ‘the place itself, where it is, is not important. It’s just a stage set.’ Sunny inside, spotted in West Norwood on a visit to see Stan in hospital, has the appearance of a choreographed arrangement of scaffolding. It is a wonderful balance of muted colour, immersive rather than dramatic. A non-descript understated scene that one can lose oneself in. Nathan has this brand of finely-tuned subtlety in his gift and it gives the work its heft, its longevity.

He is compelled to record a moment in time with its catalyst a visual sensation – an emotion that he wants to convey and make seen. Such a thing of beauty is described in Seamus Heaney’s Postcript :

Useless to think you’ll park or capture it

More thoroughly. You are neither here nor there, A hurry through which

known and strange things pass

With Heaney it is swans appearing out of nowhere, broadsiding his car in County Clare. Though it can’t be ‘captured’, emphasising the synchronicity of the moment, he nevertheless does paint a lyrical picture of the wind and light ‘working off each other’ on the ‘flaggy shore’ as the swans appear. Only a poem will do.

What obviously moves Nathan in these urban vistas is the ‘shape of the light’, the honest, recognisable and recognisably Fordian pallor of a dusky, dripping, falling English sky, the hum of an inky blue evening in south London, a flash of orange on Brighton Esplanade, a streak of trailing traffic light scored on to a twilit Norwood High Street. And there is Stan, Nathan’s late father, his hunched gait clearly recognisable, sloping along the pavement outside West Norwood crematorium, his particular piece of the stage-set illuminated with the merest touches of white on the line of the kerb. Ford, like Heaney, doesn’t shout. Only a painting will do. A painting that is as balanced as it is subtle as it is remarkable.

Aidan Quinn

January 2019.

-

London Art Fair 2025

Selected Artists 21 - 26 Jan 2025Read more -

Winter Exhibition

Selected Artists 23 Nov 2024 - 28 Feb 2025Winter Show 2024 New Paintings byJennifer Anderson, Akash Bhatt , Ruth Brownlee, Alex Callaway, Beth Carter, Andrew Crocker, Linda Felcey, Atsuko Fuji, Graham Dean, Mark Entwisle, Nathan Ford, Anna Gillespie,...Read more

Education

1997 – 2000 The Byam Shaw School of Art, BA (HONS) Fine Art

Awards

2017 Discerning Eye, Invited artist and regional prize, Mall Galleries, London.

2016 The Ruskin Prize, Walsall and London – shortlisted artist.

2015 Art in Action Oxfordshire, Best of the Best – 2nd prize.

2014 Art in Action Oxfordshire, Best of the Best – 1st prize.

2013 National Art Open, Towry Regional Prize, London and Chichester.

2011 BP Portrait Awards, Visitors Choice 2nd Prize, National Portrait Gallery, London.

2010 Royal Institute of Oil painters, Winsor & Newton Young Artist Award, 1st Prize, Mall Galleries, London.

2004 Royal Institute of Oil painters, Winsor & Newton Young Artist Award, Commendation, Mall Galleries, London.

2001, 2003 Royal Institute of Oil painters, Winsor & Newton Young Artist Award, 1st Prize, Mall Galleries, London.

1999, 2000 Royal Institute of Oil painters, Winsor & Newton Young Artist Award, 2nd Prize, Mall Galleries, London.

2001 Royal Society of British Artists, Gordon Hulson Memorial Prize, Mall Galleries, London.

1999 Young Artists’ Britain, The Prince of Wales’s Young Artists’ Award, Hampton Court Palace, London.

1998 The Worshipful Company of Painter-Stainers bursary in painting

1997 Full scholarship to study at the Byam Shaw School of Art for three years

Selected Exhibitions

2023

Solo Exhibition, Beaux Arts Bath

2021

Solo Exhibition, Beaux Arts Bath

2019

Solo Exhibition, Beaux Arts Bath

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

2018

BP Portrait Exhibition, Mall Galleries London, and touring

2017

‘Small Works for Christmas’ – Beaux Arts Bath

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

2016

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

The Ruskin Prize, The New Gallery Walsall and London.

LAPADA Art and Antiques Fair, London

2015

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

Unfurl, Gallery 1261, Denver

National Art Open, London and Chichester

Lynn Painter-Stainers Prize, London.

2014

Beaux Arts Bath, Artists of Fame and Promise

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

2013

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

National Art Open, London and Chichester

Lynn Painter-Stainers Prize, London.

2012

Beaux Arts Bath, Summer Exhibition

BP Awards, National Portrait Gallery London

Sunday Times Watercolour Competition, London

Royal Society of Portrait Painters, Mall Galleries, London.

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

Holbourne Portrait Prize, Bath. 2012

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Royal Society of British Artists, Mall Galleries, London

2011

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

BP Awards, National Portrait Gallery London

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

London Art Fair, Islington with Beaux Arts Bath

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Discerning Eye, Mall Galleries, London

Lilly Zeligman Gallery, The Netherlands

2010

Beaux Arts Bath, Summer Exhibition

BP Awards, National Portrait Gallery London

London Art Fair, Islington, London

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

Art London

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Lilly Zeligman Gallery, The Netherlands

2009

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

London Art Fair, Islington, London

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

2008

London Art Fair, Islington, London

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

‘Crossing Over’, Beaux Arts Bath

Eisteddfod, Cardiff

Royal Society of Portrait Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

2007

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

London Art Fair, Islington, London

20/21 Art Fair, Royal College of Art, London

Art London

Summer Exhibition, Beaux Arts Bath

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Victor Felix Gallery, London

2006

London Art Fair, Islington, London

Art London

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Artists of Fame and Promise, Beaux Arts Bath

Kooywood Gallery, Cardiff

2005

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

London Art Fair, Islington, London

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

‘Face Value’, Chelsea Art Gallery, Palo Alto, California, USA

Kooywood Gallery, Cardiff

Victor Felix Gallery, London

2004

Artists of Fame and Promise, Beaux Arts Bath

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Fairfax Gallery, Chelsea, London and Tonbridge Wells

Victor Felix Gallery, London

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

2003

Beaux Arts Bath, Solo Exhibition

Discerning Eye, Mall Galleries, London

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Slice 1, Jacob’s Market, Cardiff

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

2002

‘Urban Myths’, Beaux Arts Bath

Affordable Art Fair, London and New York

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Fairfax Gallery, Chelsea, London and Tonbridge Wells

Royal Society of British Artists, Mall Galleries, London

2001

Summer Show, Beaux Arts Bath

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Royal West of England Academy, Bristol

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

Royal Society of British Artists, Mall Galleries, London

2000

Royal Institute of Oil Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Discerning Eye, Mall Galleries, London

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

2001

Royal Society of British Artists, Mall Galleries, London

The Prince’s Foundation, London

Royal West of England Academy, Bristol

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

2000

New English Art Club, Mall Galleries, London

BP Awards, National Portrait Gallery, London

West Coast Art Fair, San Francisco

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

1999

Royal Society of Portrait Painters, Mall Galleries, London

Young Artists’ Britain, Hampton Court Palace, London

St. David’s Studio Gallery, Pembrokeshire

1998

‘Naked’, The Concourse Gallery, London

Worshipful Company of Painter-Stainers, Livery Hall, London